On May 16, 1871, a formidable American fleet departed Nagasaki harbor into waters that would soon become a crucible of conflict. Under the command of Rear Admiral John Rodgers, the squadron comprised five vessels: the first-rate Colorado serving as flagship, the third-rates Alaska and Benicia, and two smaller gunboats designed for river operations, Monocacy and Palos. Aboard the Colorado was Frederick Low, the American Minister to China, now entrusted with a diplomatic mission to the Korean government. The fleet's very composition reflected its dual nature - three deep-water frigates for diplomatic gravity, complemented by two shallow-draft vessels capable of navigating treacherous coastal waters.

Three days after departure, the fleet reached the Ferrieres Islands off the Korean coast. Their progress northward was immediately hampered by thick fog banks that cloaked the unfamiliar coastline, forcing the vessels to proceed with extreme caution. It wasn't until May 23rd that they finally dropped anchor near what their French charts labeled as Eugenie Island (Ippado in Korean). The anchorage, which Rodgers would name "Roze Roads" in honor of the French admiral who had first surveyed the area in 1866, lay forty-four kilometers from their ultimate destination of Boisée Island (Jagyak Island).

Without delay, Rodgers organized a comprehensive reconnaissance operation. On May 24th, he dispatched Commander H.C. Blake to lead an expedition comprising the Palos and four steam launches. The launches were commanded by seasoned officers: Lieutenant Commanders C.M. Chester and L.H. Baker, and Lieutenants W.W. Mead and G.M. Totten. Their mission was to examine the channel leading to their intended anchorage above Boisée Island, taking soundings of the waterway and surveying the neighboring shores. While Blake's group probed northward, other parties from the remaining ships conducted careful surveys around Roze Roads, meticulously mapping the surrounding waters.

These survey teams encountered local Koreans who appeared welcoming, giving no indication of the hostilities to come. During one such meeting, the Americans received a note written in Chinese characters, inquiring about their identity and purpose. Through their interpreter, they sent an informal reply stating they were Americans who had come in peace, seeking only to meet with government authorities. The response was deliberately measured, offering only basic information while emphasizing their peaceful intentions.

The fleet attempted to move north on May 29, but again the fog intervened, forcing them to anchor short of their objective. The following day, under clearer skies, they finally reached their destination, anchoring between Boisée Island and Guerrière Island. Shortly after dropping anchor, the Americans observed a Korean vessel approaching the Colorado, its occupants signaling their desire to communicate. These messengers carried welcome news: the Korean government had received their earlier communication and would send three envoys the next day for discussions.

The diplomatic meeting of May 31 was meticulously recorded in the Colorado's deck log by Lieutenant Hugh McKee, whose own role in the coming conflict would prove tragically significant. Three Korean officials came aboard – two wearing dark blue robes denoting third rank, one in light blue marking him as fifth rank – accompanied by twenty lower-ranking attendants. The Americans' failure to recognize the significance of these ranks would contribute to the misunderstandings that followed.

While the American fleet was still crossing the Pacific, careful preparations were already underway in Korea. In the northern border region of Hoeryeong, General Eo Jae-yeon had spent four years secretly training an elite force of tiger hunters. These men were renowned for their marksmanship - when hunting actual tigers, they had to kill with a single shot or forfeit their lives to the wounded beast's fury.

Eo took extraordinary care in preparing these troops, not only training them militarily but living among their families, getting to know their parents, wives and children. Though he knew from the start he was preparing them for sacrifice, his heart was heavy with the burden. Most of the young men from around Hoeryeong had followed him south, leaving behind only the elderly, women and children to gaze anxiously at the southern skies.

Unlike regular Korean troops, who were poorly trained and equipped, these tiger hunters were masters of their weapons. Though their matchlock muskets had an effective range of only 50 meters compared to the Americans' 900-meter reach, they knew exactly how to use them to lethal effect. They also brought with them an indomitable spirit that would later astonish their opponents.

The Americans would face one of the most sophisticated coastal defense networks in East Asia. Located at the mouth of the Han River, Ganghwa Island served as Seoul's western shield throughout the Joseon period. The island's strategic importance had been painfully demonstrated during the Manchu invasion of 1636, when enemy forces successfully crossed the Yeomha River and captured the island. This traumatic experience spurred the development of an increasingly sophisticated defensive network, particularly during the reigns of Kings Hyojong and Sukjong.

The defensive system followed a clear three-tiered hierarchy. At the top were the military bases (jin), commanded by high-ranking officers and serving as primary command centers. Below these were the fortifications (bo), smaller but still significant installations commanded by special commanders. The foundation of the system consisted of the batteries (dondae) – the actual firing positions that formed the front line of coastal defense.

By 1871, twelve major command centers ringed the island's coastline, collectively controlling 54 batteries arranged at strategic intervals. The spacing between these positions was particularly dense along the eastern shore facing the Yeomha River, where batteries were positioned at roughly one-kilometer intervals to create interlocking fields of fire.

The eastern coast of Ganghwa, facing the strategically crucial Yeomha River, featured the most sophisticated segment of this defensive system. From north to south, four major complexes dominated this eastern shield. The Yongjin Base commanded three batteries designed to cover the approach from the Han River confluence. The Gwangseong Fortification, with its impressive Anhaeru gate pavilion, controlled three batteries situated to defend a particularly narrow section of the Yeomha River. The Deokjin Base complex guarded the treacherous Sondolmok passage, while the Choji Base complex formed the southern anchor of this formidable defensive line.

Supporting these island fortifications was the mainland Deokpo Garrison, which maintained a substantial force of 427 naval troops and operated an impressive fleet including two defense ships, one warship, and three patrol boats. This mainland position allowed Korean forces to create dangerous crossfire zones with the island's batteries.

The construction of these fortifications represented the height of Joseon military engineering. Archaeological investigations have revealed standardized construction methods that demonstrated remarkable sophistication. The process began with meticulous site preparation, exposing weathered bedrock across the entire construction area and creating perfectly leveled foundations through careful cut-and-fill techniques.

The batteries themselves, typically measuring 100-120 meters in circumference, showcased advanced military architecture. Each housed three to four gun emplacements designed with remarkable attention to detail. The gun rooms measured approximately one meter wide, four meters long, and one and a half meters high, with square gun ports measuring roughly 35 centimeters on each side. Stone-paved floors provided stability for the artillery, while diagonal carved stones managed cannon blast effects. Many batteries along the western coast featured unique "ear rooms" (ibang) for ammunition storage.

Minister Low, however, made a calculated diplomatic decision. As Minister Plenipotentiary, he would only negotiate with officials of the highest rank who could speak for their government. Through his secretary Drew, the Americans reiterated their peaceful intentions and announced their plan to survey the Salt River (Ganghwa Straits). They offered twenty-four hours' notice so word could be sent to the local population about their non-hostile purpose.

The Korean envoys' response – or lack thereof – would prove crucial to the unfolding events. When presented with the survey plans, they neither objected nor assented, maintaining an ambiguous silence that the Americans would fatefully misinterpret. The Americans took this silence as tacit approval, but they had stumbled into a serious cultural misunderstanding. In Korean diplomatic protocol, agreement required explicit written consent, especially for military-sensitive areas like the straits. Even Korean fishing boats needed written permission to navigate these waters. This cultural disconnect would soon have dire consequences.

On June 1, the survey force moved up the Ganghwa Straits in what they believed was a sanctioned mission. Commander Blake led the expedition, with the Monocacy under Commander Edward P. McCrea, the Palos, and four steam launches. The larger wooden frigates remained at anchor, their deep drafts unsuitable for the shallow, rock-strewn channel. The Monocacy and Palos, though smaller, were well-suited for river operations, and had been strengthened by borrowing 9-inch shellguns from the frigates.

About five kilometers up the straits, the waterway bends sharply around a peninsula jutting from the island, crowned by Yongdudondae (Dragon Head Fortress). Here, the tides surge through the narrows with fearsome strength, rising and falling 9 to 10.5 meters with each cycle. The violent currents made ship handling extremely difficult, requiring precise timing and skilled navigation. This challenging stretch of water would become the scene of the first armed confrontation.

As the American vessels fought the current around this bend, the morning erupted in gunfire. Hidden batteries on both shores opened up, their guns arranged in tiers up the hillsides and fired by powder trains. Although the ancient smoothbore artillery pieces lacked both accuracy and impact - their shots mostly bounced harmlessly off the ships' rigging - the surprise was complete. In the chaos of maneuvering in the swift current, the Monocacy struck a submerged rock, beginning to leak badly. Only two Americans were wounded: James A. Cochran and John Somerdyke, ordinary seamen in the Alaska's launch. The expedition returned fire, then withdrew to report the encounter, their escape aided by the very currents that had made their advance so difficult.

The Americans viewed this as a treacherous ambush from masked batteries, a violation of what they believed was a diplomatic understanding. From the Korean perspective, however, they were simply defending their waters from unauthorized foreign intrusion - just as any nation would protect its strategic waterways. Rodgers dispatched a message demanding both explanation and apology for the attack on their survey party. He set a ten-day deadline, chosen partly to allow time for response but also to wait for the neap tides when the strait's fearsome currents would be less dangerous for any military operation that might prove necessary.

The only reply was a provocative one – a raft floating downstream laden with cows, chickens, and eggs, accompanied by a dismissive note suggesting the Americans would need provisions for their journey home. It was neither the explanation nor the apology Rodgers sought. Even more telling was the Korean prefect's written response, which proudly defended the ambush as entirely appropriate for a four-thousand-year-old civilization protecting its territory.

As the deadline approached, the Americans prepared their response. Commander Blake began organizing a landing force, knowing they would need to wait for the neap tides when the strait's treacherous currents would be more manageable. The Monocacy received temporary repairs to stop its leaking, and plans were drawn up for a more substantial retaliatory action.

On June 10th, the Americans launched their retaliatory expedition. The force included 546 sailors and 105 Marines supported by seven howitzers. The landing proved challenging due to extensive mudflats that required extraordinary effort to cross. Between the water and firm land lay a broad belt of soft mud traversed by deep gullies. Men sank to their knees in the tenacious clay, losing shoes, gaiters, and even trouser legs. The guns sank above their axles, requiring 75-80 men to drag each piece through.

The Marines led the advance as skirmishers, systematically capturing and destroying Korean fortifications. Each fort's construction revealed the sophistication of Korean military engineering - carefully prepared foundations, precisely engineered gun emplacements, and sturdy stone walls. Yet these traditional defenses proved vulnerable to modern naval artillery and determined infantry assault.

The decisive engagement occurred on June 11th at the main Korean citadel. The Americans advanced methodically, with Marines in the lead as skirmishers. The final assault focused on the Sondolmok fortress, which measured approximately 32 meters in diameter. Originally designed for a small garrison, it now held about two hundred defenders - far beyond its intended capacity.

Lieutenant Hugh McKee led the final charge, becoming the first to scale the fortress walls. Although mortally wounded by a musket ball and spear thrust, his sacrifice inspired others to follow. Lieutenant Commander Winfield Scott Schley was close behind, shooting down McKee's attacker. What followed was thirty minutes of desperate hand-to-hand combat.

In the center of the defense stood General Eo Jae-yeon himself. When his sword shattered, he seized two iron cannonballs and continued fighting. His brother Eo Jae-sun fought beside him, while nearby, two Imperial Guard troops had tied themselves to the command flagpole with their sashes, determined to defend it to the death.

The final moments were fierce. Private James Dougherty engaged General Eo in personal combat. The Korean commander shouted "You wretch!" and swung the iron cannonballs he held, but Dougherty's bayonet proved faster. As he felt the fatal wound, Eo had no regrets - he had done everything possible to defend his country and had managed to save many lives by sending away the bulk of his forces earlier.

The human cost was significant. The Americans lost Lieutenant Hugh McKee, Private Denis Hanrahan, and Landsman Seth Allen, with ten others wounded. Korean casualties were far higher - 243 confirmed dead on the battlefield with estimates of total casualties around 350. Among these were General Eo Jae-yeon and many of his tiger hunters from Hoeryeong.

The events of 1871 left lasting marks on both nations. Although the Americans achieved tactical victory, they withdrew without securing their diplomatic objectives. Korea maintained its independence and policy of isolation for several more years, becoming the only Asian nation to successfully resist Western military pressure during this period. This independence would prove temporary - within a few years, Japan would begin the process that would eventually end Korean sovereignty.

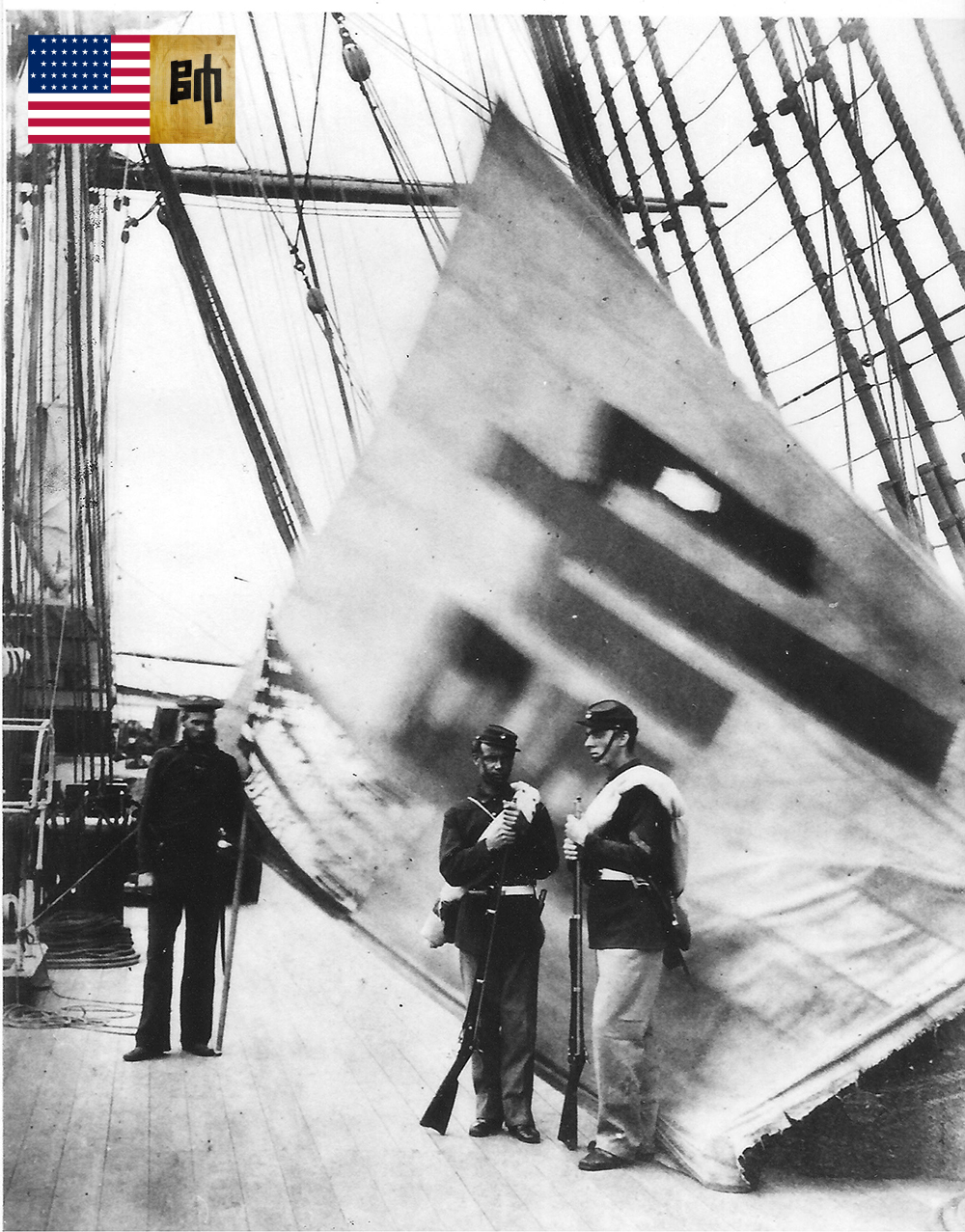

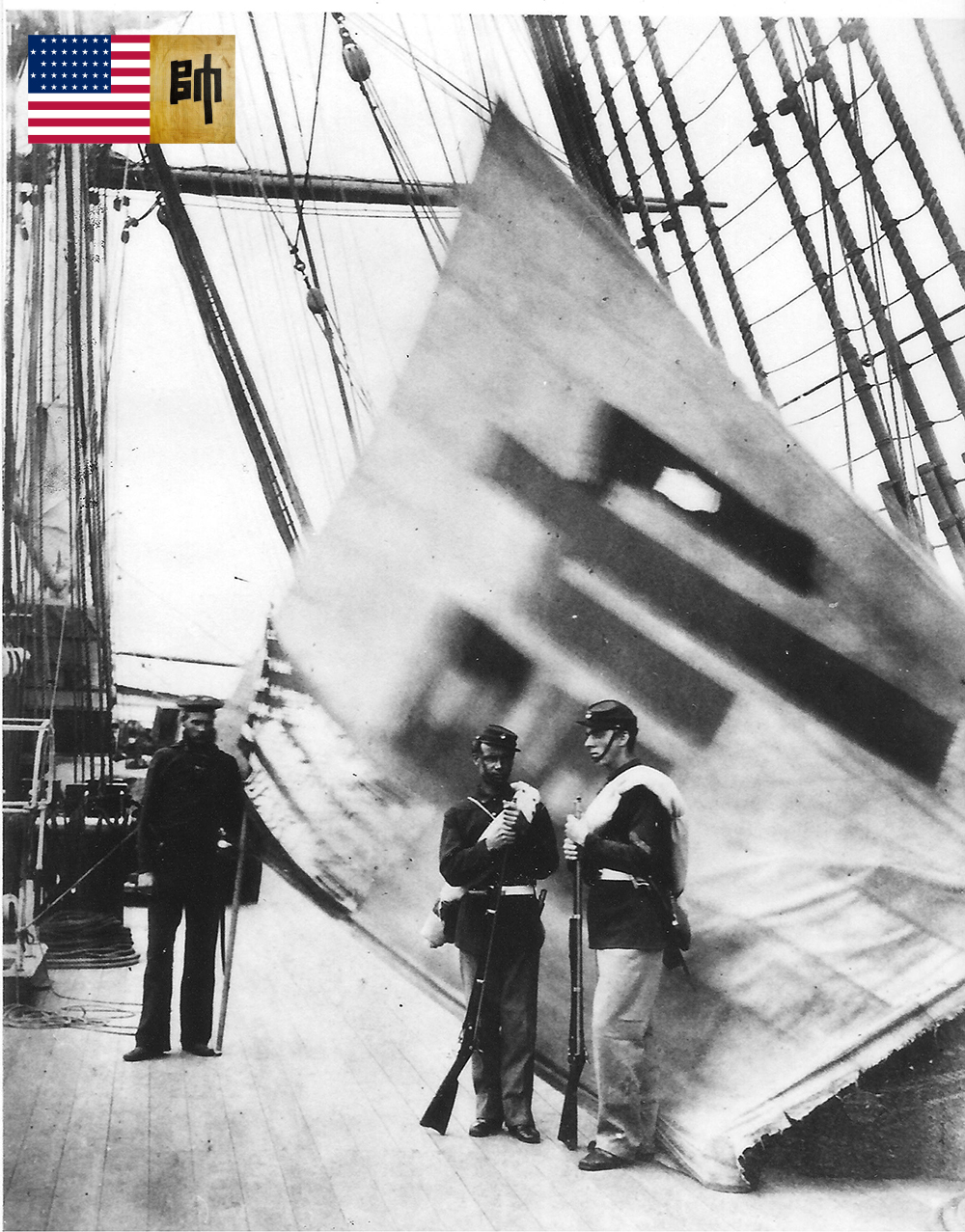

Perhaps most poignant was the fate of the Korean command flag captured during the battle. The massive hemp banner, bearing the Chinese character 帥 (su, meaning "general") in black on a yellowish background, carried both shell holes and bloodstains from the Imperial Guard troops who died defending it. Known to Koreans as the sujagi or janggungi (general's flag), it was captured by Private Hugh Purvis of the Alaska and Corporal Brown of the Colorado.

After its capture, the flag was taken to the United States Naval Academy Museum, where it remained for over a century despite Korean requests for its return beginning in the 1970s. The United States consistently refused these requests, concerned that returning "war prizes" would set an unwanted precedent. A breakthrough finally came in 2007 through a creative solution - a museum-to-museum long-term loan agreement. On October 19, 2007, the flag returned to Korean soil for the first time in 136 years, with a ceremony marking its homecoming at the National Palace Museum in Seoul three days later. Each year on the lunar date of General Eo's death, April 24, dignitaries would raise a reproduction of the flag near Sondolmok fortress where he fell. In early 2024, the original flag returned to the United States Naval Academy Museum for a three-year special exhibit, though its final disposition remains uncertain at this writing.

1871년 5월 16일, 강력한 미국 함대가 곧 충돌의 도가니가 될 수역으로 나가사키 항을 출발했다. 존 로저스 해군 소장의 지휘 아래, 함대는 기함인 1등급 함선 콜로라도호, 3등급 함선 알래스카호와 베니시아호, 그리고 강 작전용으로 설계된 두 척의 소형 포함 모노카시호와 팔로스호로 구성되었다. 콜로라도호에는 조선 정부와의 외교 임무를 맡은 프레더릭 로우 주중 미국 공사가 탑승했다. 함대의 구성 자체가 이중적 성격을 반영했다 - 외교적 위엄을 위한 세 척의 대양함과 함께 위험한 연안 수로를 항해할 수 있는 두 척의 저흘수 선박이 보완적으로 배치되었다.

출발 3일 후, 함대는 조선 해안의 페리에르 군도(현 덕적군도)에 도착했다. 북쪽으로의 진행은 익숙하지 않은 해안선을 가리는 짙은 안개로 인해 즉시 방해를 받았고, 함선들은 극도로 주의하며 전진해야 했다. 프랑스 해도에 외젠 섬(현 입파도)으로 표시된 곳 근처에 닻을 내린 것은 5월 23일이 되어서였다. 로저스는 이 정박지를 "로즈 로드"라고 명명했는데, 이는 1866년에 이 지역을 처음 조사한 프랑스 제독의 이름을 따른 것이었다. 이곳은 그들의 최종 목적지인 보아제 섬(현 자적도)에서 44킬로미터 떨어진 곳이었다.

지체 없이 로저스는 종합적인 정찰 작전을 조직했다. 5월 24일, 그는 H.C. 블레이크 중령에게 팔로스호와 네 척의 증기선을 이끌도록 명령했다. 증기선들은 경험 많은 장교들이 지휘했다: C.M. 체스터와 L.H. 베이커 중령, W.W. 미드와 G.M. 토튼 소령이었다. 그들의 임무는 보아제 섬 위쪽의 예정된 정박지로 이어지는 수로를 조사하는 것이었으며, 수로의 수심을 측량하고 주변 해안을 조사했다. 블레이크의 그룹이 북쪽을 탐사하는 동안, 다른 함선들의 팀들은 로즈 로드 주변을 세밀하게 측량하며 주변 수역의 지도를 작성했다.

이 조사팀들은 현지 조선인들과 만났는데, 그들은 앞으로 다가올 적대적 상황을 전혀 암시하지 않고 우호적으로 보였다. 한 번의 만남에서 미국인들은 한문으로 쓰인 문서를 받았는데, 이는 그들의 신원과 목적을 묻는 내용이었다. 통역관을 통해 그들은 자신들이 평화롭게 온 미국인이며, 단지 정부 당국자들과의 회견을 구한다는 내용의 신중한 답변을 보냈다. 이 답변은 의도적으로 절제되어 있었으며, 기본적인 정보만을 제공하면서 평화적 의도를 강조했다.

함대는 5월 29일 북쪽으로 이동을 시도했으나, 다시 안개가 끼어 목표지점에 못 미쳐 정박할 수밖에 없었다. 다음 날, 맑아진 하늘 아래 마침내 목적지에 도착하여 보아제 섬과 게리에르 섬 사이에 정박했다. 정박 직후, 미국인들은 콜로라도호로 접근하는 조선 선박을 목격했는데, 승선자들은 의사소통을 하고 싶다는 신호를 보냈다. 이 전령들은 반가운 소식을 가져왔다: 조선 정부가 그들의 이전 통신을 받았으며 다음 날 세 명의 사신을 보낼 것이라는 내용이었다.

5월 31일의 외교 회담은 이후 비극적인 역할을 하게 될 휴 맥키 소령이 콜로라도호의 갑판 일지에 세세히 기록했다. 세 명의 조선 관리가 승선했는데 - 3품을 나타내는 감청색 관복을 입은 두 명과 5품을 나타내는 하늘색 관복을 입은 한 명이었으며, 이들과 함께 20명의 하급 수행원들이 동행했다. 미국인들이 이러한 품계의 중요성을 인식하지 못한 것이 이후의 오해를 야기하는 데 기여했다.

미국 함대가 태평양을 건너오는 동안, 조선에서는 이미 신중한 준비가 진행되고 있었다. 북방의 회령 지역에서 어재연 장군은 4년간 정예 포수들을 비밀리에 훈련시켰다. 이들은 사격 실력으로 유명했는데 - 실제 호랑이를 사냥할 때는 한 발로 죽여야 했으며, 그렇지 않으면 부상당한 맹수에게 목숨을 잃을 수 있었다.

어재연은 이 군사들을 준비시키는 데 특별한 주의를 기울였다. 군사 훈련뿐만 아니라 그들의 가족들과 함께 살면서 부모, 아내, 자녀들을 알아가기도 했다. 처음부터 그들을 희생을 위해 준비시키고 있다는 것을 알고 있었지만, 그의 마음은 그 부담으로 무거웠다. 회령 주변의 젊은이들 대부분이 그를 따라 남쪽으로 갔고, 노인들과 여자들, 아이들만이 남아 남쪽 하늘을 불안하게 바라보았다.

훈련과 장비가 부실했던 일반 조선군과 달리, 이 포수들은 자신들의 무기를 완벽하게 다룰 수 있었다. 그들의 화승총은 미국인들의 900미터 사거리에 비해 단지 50미터의 유효 사거리를 가졌지만, 그들은 이를 치명적으로 사용하는 방법을 정확히 알고 있었다. 또한 그들은 후에 적들을 놀라게 할 불굴의 정신도 지니고 있었다.

미국인들은 동아시아에서 가장 정교한 연안 방어망 중 하나와 마주하게 될 것이었다. 한강 하구에 위치한 강화도는 조선 시대 내내 서울의 서쪽 방패 역할을 했다. 섬의 전략적 중요성은 1636년 병자호란 때 적군이 염하를 건너 섬을 점령했을 때 아프게 입증되었다. 이 트라우마적인 경험은 효종과 숙종 시기에 더욱 정교한 방어망 개발을 촉진했다.

방어 체계는 명확한 3단계 계층 구조를 따랐다. 최상위에는 고위 장교들이 지휘하며 주요 지휘 센터 역할을 하는 진이 있었다. 그 아래에는 특별 지휘관이 이끄는 더 작지만 여전히 중요한 시설인 보가 있었다. 체계의 기초는 연안 방어의 최전선을 형성하는 포대인 돈대로 이루어졌다.

1871년까지 열두 개의 주요 지휘 센터가 섬의 해안선을 둘러싸고 있었으며, 총 54개의 포대가 전략적 간격으로 배치되어 있었다. 이러한 배치는 특히 염하강을 마주보는 동쪽 해안을 따라 매우 밀집되어 있었는데, 약 1킬로미터 간격으로 포대들이 위치하여 서로 교차하는 사격 범위를 형성했다.

전략적으로 중요한 염하강을 마주보는 강화도의 동쪽 해안에는 이 방어 체계의 가장 정교한 부분이 있었다. 북에서 남으로, 네 개의 주요 방어시설이 이 동쪽 방패를 지배했다. 용진진은 한강 합류점에서 접근하는 것을 막기 위해 설계된 세 개의 포대를 지휘했다. 인상적인 안해루 문루를 가진 광성보는 염하강의 특히 좁은 구간을 방어하기 위해 배치된 세 개의 포대를 통제했다. 덕진진 복합체는 위험한 손돌목 수로를 지켰고, 초지진 복합체는 이 강력한 방어선의 남쪽 닻 역할을 했다.

이러한 섬의 요새들을 지원하는 것은 본토의 덕포진이었는데, 이곳은 427명의 수군과 두 척의 방어선, 한 척의 전함, 세 척의 순찰선으로 구성된 인상적인 함대를 운영했다. 이 본토 진지는 조선군이 섬의 포대들과 위험한 교차 사격 구역을 만들 수 있게 했다.

이러한 요새들의 건설은 조선 군사 공학의 정점을 보여주었다. 고고학적 조사는 놀라운 정교함을 보여주는 표준화된 건설 방법을 밝혀냈다. 과정은 전체 건설 구역의 풍화된 기반암을 노출시키고 신중한 절토와 성토를 통해 완벽하게 수평을 맞춘 기초를 만드는 것으로 시작되었다.

포대 자체는 보통 둘레가 100-120미터였으며, 발전된 군사 건축을 보여주었다. 각각은 세심한 주의를 기울여 설계된 3-4개의 포좌를 갖추고 있었다. 포좌는 폭 약 1미터, 길이 4미터, 높이 1.5미터였으며, 한 변이 약 35센티미터인 정사각형의 포구를 가졌다. 석조 바닥은 대포의 안정성을 제공했고, 대각선으로 깎은 돌들은 포격의 영향을 관리했다. 서쪽 해안을 따라 있는 많은 포대들은 독특한 탄약 저장소인 이방을 가지고 있었다.

그러나 로우 공사는 신중한 외교적 결정을 내렸다. 전권대사로서 그는 오직 정부를 대표하여 발언할 수 있는 최고위 관리들과만 협상하기로 했다. 비서관 드류를 통해 미국인들은 그들의 평화적 의도를 재차 강조하고 염하(강화해협)를 측량할 계획을 알렸다. 그들은 현지 주민들에게 비적대적 목적을 알리기 위해 24시간의 통보 시간을 제공했다.

조선 사신들의 반응 – 또는 반응의 부재 – 는 앞으로 전개될 사건들에 결정적인 영향을 미치게 될 것이었다. 측량 계획이 제시되었을 때, 그들은 반대도 동의도 하지 않은 채 모호한 침묵을 지켰고, 이는 미국인들이 운명적으로 오해하게 될 것이었다. 미국인들은 이 침묵을 암묵적 승인으로 받아들였으나, 그들은 심각한 문화적 오해에 빠진 것이었다. 조선의 외교 의전에서는 특히 해협과 같은 군사적으로 민감한 지역에 대해서는 명시적인 서면 동의가 필요했다. 심지어 조선의 어선들도 이 수역을 항해하기 위해서는 서면 허가가 필요했다. 이러한 문화적 단절은 곧 심각한 결과를 초래하게 될 것이었다.

6월 1일, 측량대는 허가받은 것으로 믿고 강화해협으로 진입했다. 블레이크 중령이 원정대를 이끌었고, 에드워드 P. 맥크레아 중령지휘하의 모노카시호, 팔로스호, 그리고 네 척의 증기선이 포함되어 있었다. 대형 목조 프리깃함들은 얕고 암석이 많은 수로에는 적합하지 않아 정박한 채로 남았다. 모노카시호와 팔로스호는 비록 작았지만 강 작전에 적합했고, 프리깃함들에서 가져온 9인치 포로 더욱 강화되어 있었다.

해협을 약 5킬로미터 거슬러 올라가자, 용두돈대(용머리 요새)가 있는 섬에서 돌출된 반도를 둘러싸고 수로가 급격히 굽어졌다. 이곳에서 조수는 엄청난 힘으로 협수로를 통과하여, 매 주기마다 9에서 10.5미터의 수위 변화를 보였다. 격렬한 조류는 배의 조종을 극도로 어렵게 만들어, 정확한 타이밍과 숙련된 항해가 필요했다. 이 까다로운 수로 구간이 첫 번째 무력 충돌의 현장이 될 것이었다.

미국 함선들이 이 굽이를 돌아가며 조류와 싸우고 있을 때, 아침이 총성과 함께 밝아왔다. 숨겨진 포대들이 양쪽 해안에서 일제히 포문을 열었고, 그들의 포는 언덕 비탈을 따라 단을 이루어 배치되어 화약 심지로 발사되었다. 비록 구식 활강포들은 정확도와 위력이 부족했고 - 대부분의 포탄이 배의 밧줄에 무해하게 맞고 튀어나갔지만 - 기습은 완벽했다. 급류 속에서 조종하는 혼란 속에 모노카시호는 수중 암초에 부딪혀 심각한 누수가 시작되었다. 알래스카호의 증기선에 탄 제임스 A. 코크란과 존 소머다이크 일등수병 단 두 명만이 부상을 입었다. 원정대는 응사한 후 철수했고, 그들의 전진을 어렵게 만들었던 바로 그 조류의 도움으로 퇴각할 수 있었다.

미국인들은 이를 숨겨진 포대로부터의 배신적인 습격이자 외교적 이해의 위반으로 보았다. 그러나 조선의 관점에서는 단순히 허가받지 않은 외국 침입으로부터 그들의 수역을 방어한 것이었다 - 마치 어느 나라든 자신들의 전략적 수로를 보호했을 것처럼. 로저스는 그들의 측량대에 대한 공격에 대해 설명과 사과를 요구하는 메시지를 보냈다. 그는 10일의 기한을 설정했는데, 이는 부분적으로는 답변을 기다리기 위한 것이었지만, 또한 해협의 무서운 조류가 덜 위험한 조금 때를 기다리기 위한 것이기도 했다.

유일한 답변은 도발적인 것이었다 – 소와 닭, 달걀을 실은 뗏목이 하류로 떠내려 왔는데, 미국인들이 귀국 여정에 필요할 것이라는 조롱 섞인 쪽지가 함께 있었다. 이는 로저스가 구하던 설명이나 사과가 아니었다. 더욱 의미심장한 것은 조선 현감의 서면 답변이었는데, 이는 4천년 문명국이 자신의 영토를 보호하는 것으로서 매복 공격이 전적으로 적절했다고 자랑스럽게 변호했다.

기한이 다가오면서, 미국인들은 그들의 대응을 준비했다. 블레이크 중령은 해협의 무서운 조류가 더 관리하기 쉬운 조금 때를 기다려야 한다는 것을 알고 상륙군을 조직하기 시작했다. 모노카시호는 누수를 막기 위한 임시 수리를 받았고, 더 강력한 보복 작전을 위한 계획이 수립되었다.

6월 10일, 미국인들은 보복 원정을 개시했다. 병력은 546명의 수병과 105명의 해병대, 7문의 유탄포로 구성되었다. 상륙은 광대한 갯벌로 인해 어려움을 겪었고 이를 건너기 위해서는 엄청난 노력이 필요했다. 물과 단단한 땅 사이에는 깊은 도랑들이 있는 폭넓은 연성 진흙대가 있었다. 사람들은 무릎까지 끈적거리는 점토에 빠져 신발, 각반, 심지어 바지 다리까지 잃었다. 대포는 차축 위까지 가라앉아 각각을 끌어내는 데 75-80명의 인력이 필요했다.

해병대가 정찰대로서 선두에서 진군했고, 체계적으로 조선의 요새들을 점령하고 파괴했다. 각 요새의 건축은 조선 군사 공학의 정교함을 보여주었다 - 신중하게 준비된 기초, 정밀하게 설계된 포좌, 견고한 석벽. 하지만 이러한 전통적인 방어물들은 현대식 함포와 결연한 보병 공격에 취약한 것으로 드러났다.

결정적인 교전은 6월 11일 조선의 주요 보루에서 발생했다. 미국인들은 해병대를 선두 정찰대로 하여 체계적으로 진군했다. 최후의 공격은 손돌목 요새에 집중되었는데, 이는 지름이 약 32미터였다. 원래 소규모 수비대를 위해 설계되었으나, 이제는 의도된 수용 능력을 훨씬 넘어 약 200명의 수비대가 주둔하고 있었다.

휴 맥키 소령이 최후의 돌격을 이끌었고, 요새의 벽을 처음으로 올랐다. 비록 총탄과 창에 치명상을 입었지만, 그의 희생은 다른 이들에게 영감을 주었다. 윈필드 스콧 슐레이 중령이 바로 뒤따라 올라와 맥키를 공격한 자를 사살했다. 이어서 30분간의 처절한 백병전이 벌어졌다.

방어의 중심에는 어재연 장군 자신이 있었다. 그의 검이 부러지자, 그는 두 개의 철제 포탄을 들고 계속 싸웠다. 그의 동생 어재순이 그의 곁에서 싸웠고, 근처에서는 두 명의 금군이 그들의 띠로 지휘 깃발 기둥에 몸을 묶은 채 죽을 때까지 이를 지키기로 결심했다.

마지막 순간들은 치열했다. 제임스 도허티 일등병이 어재연 장군과 일대일 전투를 벌였다. 조선의 지휘관은 "이 망할 놈아!"라고 외치며 들고 있던 철제 포탄을 휘둘렀지만, 도허티의 총검이 더 빨랐다. 치명상을 입으며 어재연은 후회가 없었다 - 그는 나라를 지키기 위해 할 수 있는 모든 것을 했고, 더욱 중요하게는 이전에 병력 대부분을 퇴각시킴으로써 많은 생명을 구할 수 있었다.

인명 피해는 상당했다. 미국은 휴 맥키 소령, 데니스 핸러핸 일등병, 세스 앨런 수병을 잃었고, 10명이 부상을 입었다. 조선의 사상자는 훨씬 더 많았다 - 전장에서 243명이 전사한 것이 확인되었고 총 사상자는 약 350명으로 추산되었다. 이들 중에는 어재연 장군과 많은 회령의 포수들이 포함되어 있었다.

1871년의 사건들은 양국에 지속적인 흔적을 남겼다. 미국은 전술적 승리를 거두었으나 외교적 목적을 달성하지 못한 채 철수했다. 조선은 독립과 쇄국 정책을 수년간 더 유지했고, 이 시기에 서구 군사력에 성공적으로 저항한 유일한 아시아 국가가 되었다. 하지만 이 독립은 일시적인 것으로 판명될 것이었다 - 몇 년 후 일본이 조선의 주권을 종국적으로 끝내게 될 과정을 시작할 것이었다.

아마도 가장 뜻깊은 것은 전투 중에 노획된 조선의 지휘 깃발의 운명일 것이다. 누런 바탕에 검은색으로 帥 (수, 장군을 의미) 자가 쓰인 거대한 삼베 깃발에는 포격으로 인한 구멍들과 이를 지키다 죽은 금군들의 피 자국이 남아있었다. 조선인들에게 수자기 또는 장군기로 알려진 이 깃발은 알래스카호의 휴 퍼비스 일등병과 콜로라도호의 브라운 하사에 의해 노획되었다.

노획 후 이 깃발은 미국 해군사관학교 박물관으로 옮겨졌고, 1970년대부터 시작된 조선의 반환 요청에도 불구하고 한 세기 이상 그곳에 남아있었다. 미국은 "전쟁 전리품"을 반환하는 것이 원치 않는 선례가 될 것을 우려하여 이러한 요청들을 일관되게 거부했다. 마침내 2007년에 창의적인 해결책 - 박물관 간 장기 대여 협정을 통해 돌파구가 마련되었다. 2007년 10월 19일, 깃발은 136년 만에 처음으로 한국 땅으로 돌아왔고, 3일 후 서울 고궁박물관에서 귀환 기념식이 열렸다. 매년 어재연 장군의 음력 기일인 4월 24일에는 관리들이 그가 전사한 손돌목 요새 근처에서 이 깃발의 복제본을 게양했다. 2024년 초에 원본 깃발은 3년간의 특별 전시를 위해 미국 해군사관학교 박물관으로 돌아갔으나, 이 글을 쓰는 현재 최종적인 처리 방안은 불확실한 상태로 남아있다.